Entrepreneurship and the Spirit of Adventure

Stories of past adventurers show what’s missing in today’s culture—and how to fix it

Many people today argue that we need to reshore manufacturing to boost the economic fortunes of the working class.

Retaining the ability to produce physical goods is important even to 21st-century economies. We do need to ensure that we are producing strategically significant materials and products domestically.

But real economic progress comes through technological innovation, productivity improvements, and entrepreneurship.

The Decline of Entrepreneurship

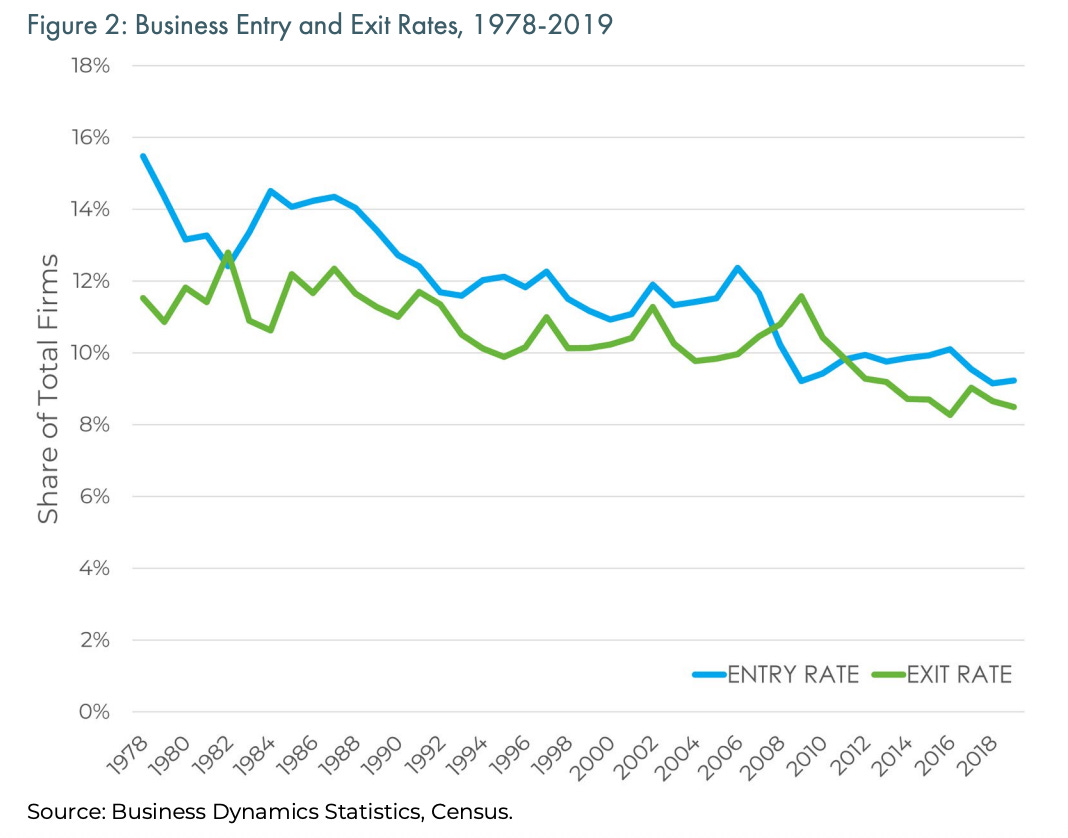

I want to focus on entrepreneurship specifically. A lot has been written about a long-term decline in entrepreneurship. Here’s a chart from a 2020 Joint Economic Committee report on the topic.

The report notes, “Declining business formation is well documented in the academic literature, which also finds young firms are less likely to become highly productive growth firms, especially since 2000.”

I have visited many urban leaders around the country and spoken at many economic development events. A consistent theme is a desire for more startup businesses, and the perception that there are significant barriers to this today.

Not all declines in entrepreneurship are necessarily bad. Having more consolidation can lead to fewer, larger, more productive and efficient firms. We are no longer a nation of mom and pop operations. As much as I like the “small, local, independent” shop, there’s a reason why those went away.

The Spirt of Adventure

Still, there does seem to be something that’s changed in the American character with regard to entrepreneurship. Part of it is the loss of what I call “the spirit of adventure.”

Consider Amway founders Rich DeVos and Jay Van Andel. When they were 14 and 16, they were commissioned to drive two trucks cross country by themselves from Michigan to Bozeman, Montana. I’m not sure how that was even legal.

Later, after college, they decided to go sailing around the Caribbean, even though neither of them knew how to sail. They bought a boat and tried it anyway. The boat sank and they had to be rescued by a passing ship off the coast of Cuba. But rather than returning home defeated, they spent the next five months exploring Latin America.

The pair also tried out a number of businesses before starting Amway. They started a flight school, even though neither of them knew how to fly. They ran a drive-in selling burgers, a toy factory, and some kind of import/export business. Probably other things, too.

There’s a link between being willing to try sailing around the Caribbean when you don’t even know how to sail and starting all these businesses, one of which eventually hit it big.

It strikes me that people of that generation were just more likely to do things like this. In his book The Vanishing American Adult, Ben Sasse tells the story of how his father, as a teenager, used to head up to Canada with friends every summer. They would spend a week canoeing around remote lakes, fishing, and dodging bears. They slept on one island and put their food on another at night to protect themselves. No older adults, no GPS, no cell phones.

I don’t hear nearly as many stories like this from Americans today. Where I do hear them is from immigrants.

To be clear: our immigration system is not working for our country and our people. We need stricter enforcement of our laws around it, and large reductions in legal immigration. But most immigrants as individuals are great people. With the official number showing that there are around 50 million foreign-born people in the country, there are more than a few bad apples in the bunch. There are a whole lot of horrible people in there. But that’s still a minority as a share of this very large population.

Some of their stories can be inspiring. I knew an architect in New York who grew up in Bulgaria. She had a burning desire to get out of her village and come to America and make it big. But she didn’t have enough money to go to college in America. Eventually, she saved up enough money to pay for one year of school at Texas Tech. She flew to Lubbock, and, being broke, she started walking from the airport to the college. A local guy in his pickup saw her dragging a suitcase down the side of the highway and gave her a ride to campus. Somehow, she figured out how to pay for her entire degree.

I don’t know if she’ll ever start a business, but many immigrants do. One reason is that international migration itself is an entrepreneurial act.

How many Americans do things like this today? Some, to be sure, but my impression is that it’s much less common than it used to be.

There are a number of trends that work together to suppress the spirit of adventure in America. One is the aging of our society. Older people are just less adventurous and dynamic than younger ones. That’s the cycle of life. But there are others that affect even younger people today.

Helicopter Parenting

The first is the rise of helicopter parenting. It’s no secret that children today have far less freedom and far less unstructured time than previous generations did. My Generation X was the last generation of “free range kids” who could be out and about on our own without parental supervision.

Today, parents can get arrested for letting their kids walk to the playground at the end of the block by themselves. It’s not just that the police and child protective services will do this but that there’s an army of busybodies out there just waiting to call the cops on parents doing things they don’t approve of.

Children today also spend much more of their time in structured, programmed activities versus spontaneous play with peers. Declining childbirth rates also mean there are just fewer peers to play with.

Everything about the way kids are raised today discourages them from being adventurous. Except, of course, for participating in specially curated adventures selected and programmed for them by others for developmental enrichment.

Digitization

For the youngest generations, digitization also plays a role. Simply put, today’s young people are finding their adventures in the virtual world, not the physical one. They aren’t driving a truck cross country at age 14. They are too busy spending hours on Roblox or TikTok.

Many parents think this is a good thing. There’s still a perception that the primary dangers to children are in the outside world, from things like child predators or school shooters. They underestimate the extent to which the real dangers today are in the digital world. They’d be happier if their kids spent hours per day online than if they drove a truck cross country, went fishing off the grid in Canada, or went sailing in the Caribbean.

The Regulatory State

A third factor is our metastasizing regulatory state. There’s an expression on the internet that, “You can just do things.” Unfortunately, today we too often can’t just do things.

Previously, when we wanted to build a new road, we just built it. We built the Hoover Dam in the 1930s without even being entirely sure how we were going to build it. We put up the Empire State Building in just a bit over a year.

This kind of freedom definitely came with costs. Highways did incredible damage to many urban neighborhoods, and displaced untold thousands of people who had no voice in what happened to them. Deaths on job sites and in factories were common. Eleven people died building the Golden Gate Bridge. Pollution reached extreme levels, with the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland infamously catching fire.

It was reasonable for our society, as it got richer, to become less tolerant of such things. But the result was an extreme culture of safetyism, citizen voice, veto points, judicial activism, and regulation that makes doing almost anything extremely difficult and costly. It can take a decade to even get permission to build a new highway these days.

One reason that so much entrepreneurship has gone into the digital world is that it has been one of the few areas without this regulatory thicket. In fact, we passed many pieces of legislation to do things like exempt online platforms from liability for user-generated content, exempt e-commerce from taxation, etc. No surprise, this industry boomed.

Today, the regulators are now circling the digital world as well, such as the many interest groups that want to essentially set themselves up as overseers of the AI industry.

While perhaps this is more directly related to entrepreneurship itself than the spirit of adventure, along with helicopter parenting, this has instilled a mindset of having to ask permission in order to do anything, of compliance over adventure.

Credentialism

Then there’s the rise of credentialism. Starting with my generation, the script for success in life became to go college and get a job at a large, prestigious white-collar employer.

Post Generation X, competition to get into college grew enormously, and the cost did, too. Thus, children growing up are channeled from an early age into a tedious process of résumé building and following the script to get into the right college, which will then get you into the right job.

In this environment, anything that doesn’t contribute toward getting into a higher tier of college is viewed as a poor use of time. Entrepreneurship in this environment is only something you’d do to burnish your résumé to get into Harvard. Just as one example, I periodically read articles in my town newspaper about high schoolers who have created some non-profit. While the cause may be nominally good, it seems likely that the real reason they are doing it - and pitching the story to the media to validate the project - is for college application purposes.

This environment breeds a mentality of compliance, script following, and cynicism. It doesn’t create an environment for genuine adventure or doing things that are truly off script.

Even the process of high-value entrepreneurship seems a bit scripted today. You buy a hoodie or whatever the uniform of the day is. You put together your pitch deck with a hockey stick diagram and total addressable market. You get angel investors. You issue SAFEs. You apply to accelerators. You do your seed round, series A, series B, etc. Capital tends to flow into approved types of businesses. (Think about how it took Elon Musk’s success with SpaceX to catalyze investibility in that sector).

There’s a lot of value in having standardized processes and lingo. Obviously, huge value is being created via Silicon Valley entrepreneurship. But from the outside, it does look somewhat designed to imitate the kinds of scripts that now dominate life paths.

Nevertheless, the tech world seems to be one of the last places left where people with an adventurous spirit are attracted. I think about Luke Farritor, the DOGE staffer who decoded a charred papyrus from Herculaneum that had been buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. A Bloomberg profile of him was designed as a hit job but managed to make him seem incredibly cool and exactly the kind of person we need much more of in America. (If you can’t access the article, I excepted it in a previous weekly digest).

Recovering the Spirit of Adventure

Farritor is an example of how Americans can still have that spirit of adventure. What we need to do is awaken it in our people, and certainly to stop snuffing it out. We need less structured parenting and more free-range kids. We need to put down our phones. We need to recognize that the scripts are increasingly not working, so maybe we need to blaze trails for new pathways.

Recovering the American spirit of adventure is a key part of restoring dynamism and entrepreneurship to our society.

Cover image: Luke Farritor by HeaB/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 4.0

Sigh. Did you have to cite Amway (which in Michigan we called Scamway) as an example? MLM firms are pyramid schemes notorious especially for preying on Christian women.

Know what’s also neat about immigrants and business? They often don’t pay taxes or obey regulations like native born Americans!

I know I know, but still we have to stop saying “immigrant” like it’s all one thing. Listen I have a lived a less than sheltered life in major urban centers here and overseas. Plenty of nice, smiling immigrants who are perfectly personable and have radically different ethics at play.

So even when you say most are “great people” you’re saying more than you know. “Not monsters” is perhaps more accurate and no one really thinks that.

I’m kind of tired of hearing about immigrants having more sterling qualities than the natives. Again back to less than sheltered it was an immigrant who changed my career for the better, I nearly married an immigrant, my mothers family was heavily immigrant. The fact that they were all Christian though is a big deal.