When the Decline of American Christianity Gets Personal

A pastor reflects on his church closing, fertility inequality, declining economic prospects for lower income white America and more in this week's roundup.

Ryan Burge is a great scholar on religion in America. He shares data driven insights in his Substack Graphs About Religion, which I highly recommend subscribing to. He’s also the author of the book The Nones: Where They Came From, Who They Are, and Where They Are Going, about those who have no particular religion.

He’s also been an American Baptist pastor for over 15 years. The trends he wrote about caught up with his own church, which just voted to shut down, a story that made the AP. He just wrote a piece sharing his own personal account of the closure.

How do you get rid of a pulpit? Or a communion table?

Does anyone want 30-year-old choir robes?

What do you do with the baptismal records of a church that dates back to the 1860s?

I never thought I would be asking myself these questions, but here I am, like many other pastors across the country as the number of Americans who belong to a faith community shrinks and churches that once housed vibrant congregations close.

What’s happened at my own church is especially poignant since in my day job I research trends in American religion. And when I first became a pastor, right out of college, there were ominous signs, but I did not foresee how quickly the end would come, hastened by a pandemic.

…

There’s an apocryphal quote from John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, that I thought about often in those first couple of years: “Light yourself on fire with passion, and people will come from miles to watch you burn.”

I tried to light that match every Sunday morning. People didn’t show up.

…

After a couple of years, the discussion about revitalizing the church began to grow quiet. A sense of resignation started to creep in. I came to a disheartening conclusion: I wasn’t going to be able to turn things around. I think at that point most members knew in their hearts that the end was coming for the church. We were just all afraid to speak that truth into existence. It was better to keep our heads down and focus on the next worship service and not worry about what would happen in three or five years.

…

What I was seeing in the data was unmistakable and mapped perfectly onto what I was seeing every Sunday — mainline Protestant Christianity was in near free fall, and the numbers of nonreligious were rising every single year.

…

I walked out those doors into the blinding heat of a summer day in southern Illinois and stepped into a future where I don’t know where I will go to church next Sunday, or even if I want to go. Frankly, I don’t know if my own faith will survive, and I’m not sure if the church in America will be there for the next generation like it was for me.

And I’m terrified because for the first time in my spiritual life, I don’t know what’s next.

Click through to read the whole thing.

Thank you for your faithful service, Ryan.

The Fertility Decline

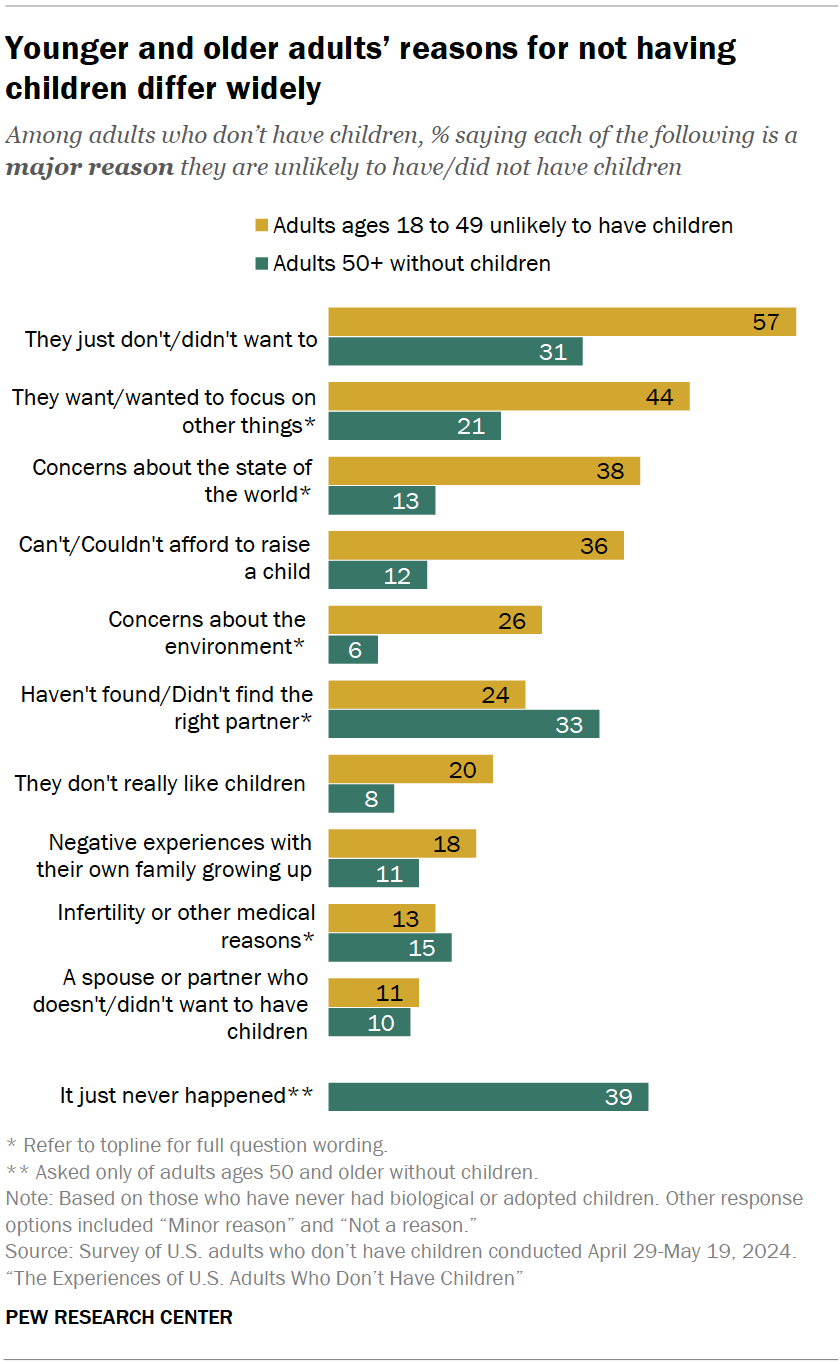

Pew Research is out with a new report on childlessness in America. The most interesting part is their survey of under 50s about this. The leading answer about why people don’t have children is that they just didn’t want them.

There’s a lot of good survey data in there, so check it out.

The Wall Street Journal ran its own article on why people don’t have children.

But unlike their parents and grandparents, the authors say, younger Americans view kids as one of many elements that can create a meaningful life. Weighed against other personal and professional ambitions, the investments of child-rearing don’t always land in children’s favor.

…

With a single mom during her early childhood and a brother 15 years her junior, Sanchez grew up helping with diaper changes and bottle feedings. Before she has kids of her own, she wants to move from the couple’s one-bedroom apartment into a bigger place. She also hopes to climb the ranks at the advertising agency where she works, ideally doubling their combined income of $100,000.

“I know what it’s like for a child whose parent wasn’t prepared for them,” says Sanchez. Still, she admits, the amount she thought she needed to earn before having children was far lower a few years ago. “It feels like a moving target,” she says.

…

Middle-class households with a preschooler more than quadrupled spending on child care alone between 1995 and 2023, according to an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics and Department of Agriculture data by Scott Winship at think tank the American Enterprise Institute.

Yet only about half of the increase is due to rising prices for the same quality and quantity of care. (Child care prices are up 180% overall since the mid-90s, according to BLS data.) The remaining half is coming from parents choosing more personalized or accredited care for a given 3- to 5-year-old, or paying for more hours, Winship says.

…

They moved to New Orleans a year ago in search of the city’s joie de vivre—and other childless millennials. With a combined income of $280,000, the couple is able to put about $4,500 a month toward what they hope will be a mid-50s retirement. Another $2,600 pays rent on a sprawling Creole townhouse. The remaining $8,000 or so—much of which they assume would have been eaten up by child-rearing—goes primarily toward enjoying their lives. The couple often dines at the city’s upscale restaurants (including two recent $700+ dinners), regularly works out at a high-end wellness center and recently paid cash for a BMW. Edenfield meditates for an hour every morning and works on the novel he’s writing at the local corner bar many nights. For companionship, the couple fosters a rotating cast of Bengal cats.

And Darel Paul at Compact wrote about “fertility inequality.”

Rather than being part of the solution, however, [Elon] Musk is in reality part of the problem. While marriage is the world’s most potent fertility strategy, only half of Musk’s children have been born inside marriage, and none of those in nearly 20 years. While assisted reproductive technologies, or ART, account for only 2 percent of US births, all of Musk’s 11 surviving children have been conceived through it. While Musk’s extreme wealth supports his very high fertility, it also contributes to wealth inequality and poverty that is itself a driver of societal-level fertility decline and fertility inequality, particularly among men. Sharing children with (at least) three different women, Musk isn’t boosting birth rates, but instead practicing a high-tech form of polygyny. He is an avatar of fertility inequality for an infertile age.

…

Fertility patterns today, especially for men, are making a return to the pre-industrial type, when a rich man could have five wives (or “partners”) and a dozen (or more) children, while a poor man could have none of either. While Musk claims to want everyone to have “big families” and insists he is “doing [his] best to help the underpopulation crisis,” his actions both as a businessman and as a father are suited for a society of simultaneous low fertility and high fertility inequality. Musk’s personal hoarding of the wealth generated by his investments undermines a more democratic distribution of male status. This undermines general fertility as more men are cast into relative poverty and have increasing difficulty both affording a child as well as even attracting a mate with whom to have a child. Using his high status to engage in personal fertility behavior bordering on the polygynous, Musk contributes to the skewed distribution of mates characteristic of polygynous societies, in which male fertility inequality is highest.

Economic Mobility Worsens for Lower Income Whites

Harvard Economist Raj Chetty is out with another one of his studies on economic mobility, backed by his proprietary access to IRS tax return data. Chetty found that upward economic mobility has degraded a lot for lower income whites in America. The Journal covered it this way:

Children born to low-income non-Hispanic white families in 1992—those at the bottom 25% by income—were less likely to move into a higher income level when they reached age 27 than children born to low-income white families in 1978 were. Poor white children born in 1992 were simply worse off than those born in 1978. (While some people move up and down the income ladder later in life, by 27 most are near the rung they will remain on.)

But the research also contains a more hopeful finding that poverty needn’t be a life sentence, with the potential for poor children’s prospects to be made better. While mobility among the children of poor white families slid backward, children born into poor Black families in 1992 were more likely to move up the economic ladder than their 1978 counterparts were.

…

This dynamic, playing out across the country, led to a significant widening of the income gap between poor and well-off white children. A white child born to parents at the 25th percentile in 1978 made, on average, an inflation-adjusted $10,383 less at age 27 than a child born to parents at the 75th percentile. But for children born in 1992, that income difference was 27% larger at $13,202.

Although lower income black Americans saw an increased likelihood of upward mobility, which is good news, there’s still a black-white gap.

This is a good example of the economic conditions underlying populism. A large segment of America has seen their economic prospects decline a lot. Remember that they next time you read someone trying to tell you that unhappiness about the economy is just “vibes.”

Best of the Web

Michael Clary’s son is turning 18. He asked people to write letters to his son sharing their life wisdom. He got 37 replies, and summarized what they had to say in this X thread.

Kay Hymowitz: New Girl Disorder - Why are young women so prominent in anti-Israel protests?

Presbyterian pastor C. R. Wiley shared some thoughts on when to leave a denomination.

A nice essay in the Point magazine about Marilynne Robinson’s Reading Genesis.

New Content and Media Mentions

This week I got a mention from Doug Wilson.

New this week:

My podcast was an interview with AEI’s Yuval Levin about his new book on the Constitution and how it can bridge society’s divides.

In American Compass, I wrote about why conservatives should care about cities.

In Governing magazine, I wrote about the under-heralded turnaround of Miami.

I wrote about how many conservative elites prefer to live in progressive cities rather than conservative areas, blue states rather than red ones.

And John Seel contributed a guest post on the world “they” made.

You can subscribe to my podcast on Apple Podcasts, Youtube, or Spotify.

I feel like a crazy person even having to type this out, but Davis and Edenfield are in the 94th percentile of US household income. The reporter should have asked them for a number that would be "enough" for them to feel comfortable having kids.

I'm sure that you could push that number well up into the seven figures if you tried. Let's say you are a professional in NYC, and you feel that you need to give each of your kids private school for 12 years, plus a family-sized apartment in Manhattan and a summer place in the Hamptons, and whatever other crazy things those kids "need" these days... How much annual income do you need for that? $2 million? $5 million?

The WSJ reporter is great, but also really should have asked them: how do you envision growing old? What do you think is going to happen when you become frail and easily confused? Do you think the all-benevolent state is going to make sure you're OK? Who do you think will check in on you?

Illustrative anecdote from Peachy Keenan below:

https://americanmind.org/salvo/childfree-doesnt-mean-pain-free/

I called the Coldwell Banker realtor on the listing—a blonde, middle-aged battleax—and discovered that this scammer was colluding with the Russian to sell Jan’s house right out from under her and dump her, penniless, onto the street. Russian collusion!

The day before escrow closed, an estate lawyer my mother found managed to scuttle the sale. The furious Russian cursed my mother, hopped into his purloined C-class, and scurried home to the wife and three children he had been supporting by stealing over $50,000 from Jan.

Jan died years later in her own home, surrounded by kindly nurses.

Her estate lawyer informed us that this happens all the time. Nursing homes are full of bewildered old women robbed blind by false suitors and elder-abusing caretakers.

Jan got lucky. You may not have the good fortune to live next door to my mother. There may be no one to intervene when the swarthy new “boyfriend” 50 years your junior makes off with all your apples, all your branches, and saws down your trunk.

The sovereignty of God rules with the decline of the American church, the loss of fertility, the diminishment of marriage. We’re trying to look at what the church is “doing wrong”. And while the church has never been perfect the world, the flesh and the devil conspire against us. Just as God warned the Israelites that after they entered the promised land taking houses they hadn’t built and vineyards they hadn’t planted, they would forget Him. So is it now in America. We can come up with all kinds of brilliant ideas to “fix things” and develop an intellectual elite that will guide us, but that will fail.

We in the church are not called to be effective, only faithful. Faithful pastors will preach the gospel. Faithful elders will disciple their families and those who are called. Faithful deacons will provide for those in need. The Holy Spirit will do the rest. Everything else is vanity.