William Lind’s 4th Generation War concept is rooted in the decline of the legitimacy of the state. He writes:

At the heart of this phenomenon, Fourth Generation war, lies not a military evolution but a political, social, and moral revolution: a crisis of legitimacy of the state. All over the world, citizens of states are transferring their primary allegiance away from the state to other entities: to tribes, ethnic groups, religions, gangs, ideologies, and “causes.” Many people who will no longer fight for their state are willing to fight for their new primary loyalty.

This isn’t just about the third world. It’s happening at some level in the US, where institutional trust is in long term decline.

How should we think about identification with, loyalty to, and investment in American institutions?

We already see that the left’s loyalty to American institutions is entirely contingent. As soon as those institutions do something they don’t like, they turn to the attack.

For example, when Donald Trump was elected President, a large number of people on the left said he was “not my President.” They declared themselves “the resistance.” Note the use of insurgency language here in line with Lind’s concept. This is a cultural form of insurgency conflict. Law professors from Yale and Harvard decry the US constitution in the pages of the New York Times. Or again, think about how many climate change activists put their cause ahead of any American considerations. Or how many want to “defund the police” or even abolish the police.

Clearly, these people think that America’s institutions are only valid to the extent those institutions are doing what they want.

I’m always struck when reading leftist writers like Herbert Marcuse, how they stridently and fundamentally viewed America as a morally illegitimate regime. The critical theorists understood that there’s great power in being willing to take a fundamentally critical stance against society’s institutions and structures of power.

How should people on the right think about American institutions?

Americans on the right have tended to be patriotic people who salute the flag, send their kids off to serve their country in the military, etc. They’ve had a lot of loyalty and identification not just with the territory of the US, or the American people or American culture, but also with our government and major civic institutions. This is one reason they get so upset when those institutions “go woke” or deviate from what they believe the institutional mission should be.

This is a problem for the right because, as I noted:

Almost all of the major powerful and culture shaping institutions of society are dominated by the left. This includes the universities, the media, major foundations and non-governmental organizations, the federal bureaucracy, and even major corporations and the military to some extent. The one truly powerful institution conservatives control, for now at least, and it’s an important one, is the US Supreme Court. The other institutions conservatives control — alternative media like talk radio, state elected office, churches — are subaltern. They are lower in prestige, power, and wealth.

This situation caused Revolver News editor Darren Beattie to provocatively ask at the NatCon 3 conference, “Can one be an American nationalist?” As he put it, “What does it mean to be a nationalist in a situation in which the nation’s dominant institutions and stakeholders have become fundamentally hostile to the would be nationalist?”

In this environment, people on the right need to rethink their relationship with American institutions.

Make no mistake. I’m an American. I love this country. I love our people – all of our people – even the haters and the losers, as they say. I love the American way of life. I don’t think we’re perfect. We have a lot of things we have done wrong in both the past and present that need to be corrected. But this my country.

At the same time, we need to take stock of reality and the current condition of our institutions.

This is an area where I am personally torn, and continue to think about a lot. But my current view is that we need to take a triage approach to the our institutions.

Some institutions are doing well, and we should reward them, invest in them, and support their leaders.

Others are in some state of decline. Perhaps some are reformable, or would do better with more public support. Others are in terminal decline. Others are not just declining, but have become actively harmful to ourselves or others.

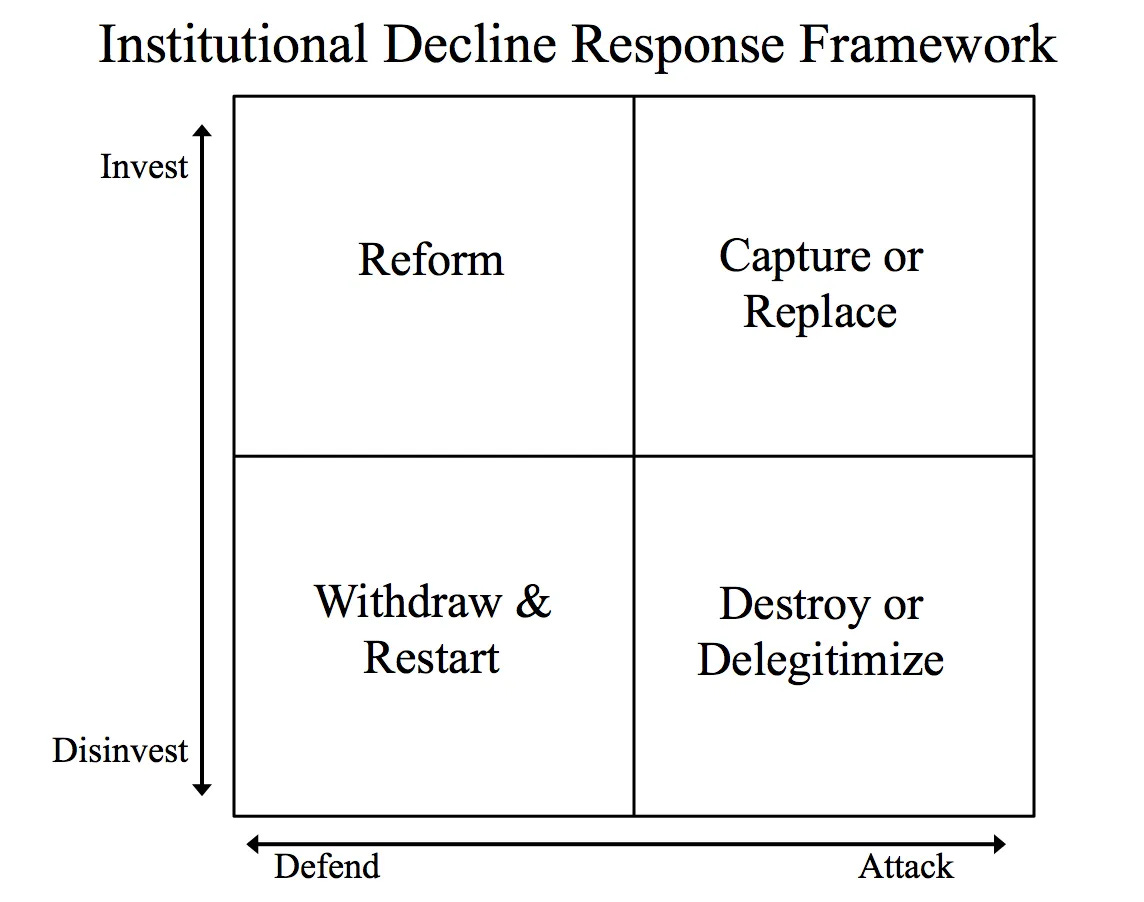

Back in newsletter #24, I talked about how we should respond to failing institutions. One of the tools I included was a 2x2 matrix I created with axes of Invest-Disinvest and Attack-Defend.

I’d encourage you to read the whole thing.

But today I want to highlight another way of thinking about it, rooted in the work of philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre. He concluded his landmark book After Virtue with this provocative closing paragraph:

A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognising fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness. If my account of our moral condition is correct, we ought to conclude that for some time now we too have reached that turning point. What matters at this stage is the construction of local forms of community within which civility and the intellectual and moral life can be sustained through the new dark ages which are already upon us. And if the tradition of the virtues was able to survive the horrors of the last dark ages, we are not entirely without grounds for hope. This time however the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

This is the paragraph from which Rod Dreher took the name of his “Benedict Option.” MacIntrye famously did not like Dreher’s application. I can’t help but wonder if he regrets writing that paragraph, because other people took it more serious than he did.

But even though I don’t think we are on the verge of a new dark age, nor do I believe that the United States is going to collapse, there are a number of guidelines we could take away from that and apply to our current situation.

First, cease identifying the continuation of the American nation and the well-being of the American people with the continuation of the current rulership and institutional structure of our society.

MacIntyre said that men of goodwill “ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that [Roman] imperium.”

This is not a call for revolution or a new constitution but to once again step up to reform our institutions and elite in ways we’ve done many times in the past.

We eliminated slavery and built a truly integrated national republic after the Civil War. We responded to the Depression and the challenges of the second industrial revolution with the New Deal. To meet the challenges of the Cold War, we created the postwar institutions ranging from NATO to the World Bank.

One might have identified America with the pre-New Deal institutional arrangements, as some early postwar conservatives did. But they abandoned this because it became untenable. It turned out that, actually, America was not identical with its 19th century economic system.

Similarly, today’s elite identify America too strongly with aging and increasingly dysfunctional institutions. We need an institutional refresh to address the challenges of 21st century America.

Similarly, we once had a WASP elite that dissolved during the 1960s and 70s. If this deeply rooted cultural, economic, and political elite could go away, then certainly many of today’s elites could likewise be swept aside in favor of new and hopefully better elites. The people who are running today’s American institutions are not entitled to rule in perpetuity.

Second, turn aside from maintaining and participating in the propping up of what some call the “Globalist American Empire.”

MacIntyre noted that men also “turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium.”

I’m Team USA all the way. But my support of America does not extent to its imperial mission abroad. The Soviet Union is long gone. In Iraq and in Libya, at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay, by imprisoning journalist Julian Assange and massacring innocent civilians with drones, the US has forfeited its moral claims about its overseas adventures.

Yes, Russia is worse. Yes, China is worse. But just because they are bad, doesn’t make us good.

I for one am glad to see enlistment in the military falling. There should never be another Libya created by US hands.

Third, recognize that the problems aren’t just out there, in some other part of the world, but they are also in here, inside America.

MacIntyre writes, “The barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time.”

America’s leaders, even conservative leaders, love to posit that our problems are of foreign origin. Today it is Russian disinformation. Yesterday it was Islamic terrorism. Before that it was the German Frankfurt School or the French post-modernists.

Obviously we have rivals abroad who mean us ill. There are plenty of bad ideologies overseas.

But we also have to face the fact that many if not most of our problems today are home grown. It wasn’t Russia that forced us to outsource our industrial base and made it impossible for us to build artillery shells at volume. France didn’t force us to build the most expensive mile of subway in the world. China didn’t make us close schools for extended periods of time and impose terrible learning loss on kids, likely adding thousands to the school to prison pipeline.

The source of most of our most critical problems is failed US leadership and failing institutions. And yes, that includes leadership on the right, which I criticize all the time.

Fourth, build new local structures to sustain community and moral life.

MacIntyre said that people embarked on “The construction of new forms of [local] community within which the moral life could be sustained.”

As this new New York Times article makes clear, the pandemic school shutdowns were a debacle for education. But the same people who imposed them still run the show in education. There’s been zero accountability for failure, and there’s no prospect of any.

Our public schools are a critical institution. Yet in all too many places they have failed. They are also almost uniformly imposing unpopular ideologies. There’s no realistic vector for the average person to be able to reform the schools. Hence we see families rationally abandoning public schools in favor of private or home schooling options. The blame here is not with them, but with those who are in charge of our public education system. Among other things, this is because they refuse to take even the smallest actions to regain or even sustain public trust.

The response in this situation and others like it is to hope for reform, but in the meantime to adopt a transactional mindset towards those institutions, and develop compensating alternatives to mitigate the damage they can cause to you and yours.

I for one haven’t given up on America and its institutions. We’ve been in far worse spots in the past - the Civil War, the Depression - and found the wherewithal to reinvent ourselves. America has had what Japanese scholar Fuji Kamiya calls “a reserve power that allows it to overcome both the inadequacies of its leaders and the foibles of its citizens.”

At the same time, we shouldn’t let the prospect of renewal or the gaslighting of others deceive us to the actions we need to take now. Again, the left already has a fully contingent view of loyalty to America and its American institutions. In a declining trust society, a transactional mindset and gaming the system have become increasingly the norm in America, alas.

Having the same sort of blind loyalty to those institutions as in the past - sending your kids off to get killed or maimed in some imperial conflict overseas without reflecting on it seriously, for example - is a mug’s game.

Again, some of our institutions in some places are still performing well and with integrity. Fortunately, we still have a number of high performing communities. Those deserve our trust and investment. But this is increasingly not the norm. The decline in trust in our institutions is entirely deserved.

Americans of all stripes need to seriously reassess their relationship with the country’s major institutions in light of how poorly so many of them are performing and the caliber of the people leading them.

Very timely that Al Mohler had a conversation very similar to this topic with Patrick Deneen.

Patrick argues persuasively that we are in an oligarchy right now and that many use the term "assault on Democracy" to protect that oligarchy.

https://albertmohler.com/2024/03/20/patrick-deneen-2/

Hyped me up there, Mr. Renn. Let's build.