The idea of “intersectionality” originated with black feminism. Black feminist activists noted that they experienced racism on account of being black and sexism on account of being women. But their experience wasn’t simply racism + sexism, but was its own unique thing as well.

One does not have to agree with the way the idea of intersectionality is applied today to recognize that there’s something valid about this basic observation. Black feminists were both out of place among white feminists and out of place among the black power activists, a male dominated milieu.

This same idea applies in many other contexts. Consider, for example, working class men. They suffer from the general challenges facing men in our society today, but also from the challenges facing the working class. As with black feminists, their experience is not simply working class + men, but has unique aspects as well.

Richard Reeves’ American Institute for Boys and Men recently released a study looking at the state of working class men.* It’s a brief eleven-page paper, but with many sobering graphs.

For example, there’s been a significant decline in the share of working class men who are actually working. In fact, non-working class women are now more likely to be employed than working class men are.

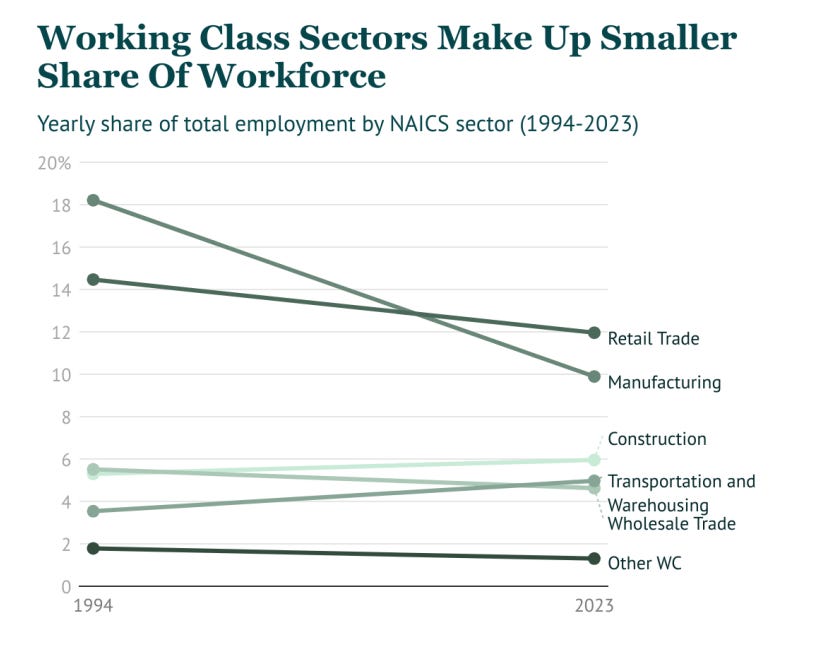

Part of that is because traditionally male dominated working class employment sectors have been in decline.

This chart on employment by race and class is revealing of the scale of the challenges. Although there’s a large white-gap black in most statistics generally, here we see that non-working class black men are significantly more likely to be employed than working class white men.

Lastly, I’ll post this chart of widening gap in deaths of despair (that is, from drugs, alcohol, and suicide), with working class men by far the highest level.

There are many other pieces of data in the report, including the reasons why working class men aren’t employed, gaps in Covid deaths and on-the-job deaths, marriage rates, and number of friendships.

How to improve this is a very serious challenge. Part of it comes from the intersectional experience I mentioned. When I was young, there was far less class separation between the working class and those with college degrees. They lived together in the same communities. They shared the common American mass market culture of that era. That is, they consumed many of the same products, watched many of the same TV shows and movies, etc.

Today, the working class and non-working class increasingly inhabit parallel worlds. The geographic, consumer habits, and mores - much of the experience of life - of the college educated are distinct from those without. The city where I live is 75% people with college degrees, for example.

Even for those of us who want to help working class men improve their fortunes, we don’t necessarily have the perspective necessary to design public policy. Nor do we even relate well to the working class on a personal level.

I grew up in a rural white working class milieu. I still enjoy hanging out in Southern Indiana and with the people there. But could I easily relate well enough to a working class man there experiencing life challenges such that I could be a help to him? Realistically, I’m not likely to become friends with someone in that situation. And if I did, I think I’d struggle to be a positive influence.

The vast majority of my readers here are college educated men, and the information I provide is mostly useful to men with degrees. The types of cultural diagnostics and self-improvement ideas I provide are not likely to be relevant to the average working class person.

People have pointed this out to me - and they are right. But it doesn’t mean I have any ideas about how to change this. (One person who is working on it is Michael Foster, whose suburban Cincinnati church is focused on what he calls “blue collar confessionalism”).

There is where the basic idea of intersectionality is relevant. Although those of us men with college degrees in theory have a certain gender solidarity with those who don’t, and do in fact have some things in common, the social class element creates a relational chasm that’s difficult to bridge given the way social classes have diverged into parallel societies in recent decades.

This makes addressing the challenges of working class men especially difficult. We must continue to try to find a way forward, but with humility.

Click over to read the whole AIBM report.

* Note for this report, working class is defined simply as: doesn’t have a college degree. This is a limited definition but a common proxy. And there’s no good way to create a robust definition that also enables you to easily slice the data that way.

This article points out something that hits home with my family. All of the men in my family are blue collar metal fabricators. Some work in constructing sheds, others work in factories. The men. The men in my family start off doing ok. My grandpa was married with children, owned his own home in a suburb close to his work, which included white collar people (although there was a lot of public housing around also). My dad and uncles all do the same line of work, but had to move a long way from their home area to some where else and commute to get to work. But they still managed to have a job for life, own their own home and raise a family. My brother has a job, but its not permanent and he lives in my parents garage. There's a lot of alcohol and even drugs have become something in my family, which weren't part of my dad or grandpa's lives. my brother and I have had our own battles with suicide. It seems like the blue collar men in my family follow this graph. A big difference though, I believe is that I have finished highschool and have a master's degree. It makes me look at the world with a series of options for what I can do and what I can learn. I think my blue collar background has made me go down many potholes in my professional career due to genuinely not understanding or having the people skills to communicate with professional people, but I have learnt from my mistakes and now I'm improving each day. My brother on the other hand all I can guess is that he sees the world as a series of deadends with no way out signs. He has no goals, and does not feel he has the capacity to achieve those goals if he tried. His wants and needs are like any other man, a stable job, the capacity to buy a house, to meet a good woman and have a family. I don't have any answers because even though were from the same background, we treading two different paths.

Get a skill, get a job, keep a job, and don't have a kid till you are married. The wealthiest members of my extended family never went to college, or if they attended, did not graduate. What they did do was get a trade, show up sober to work, and get married prior to having kids.

Their kids have gotten a trade (often the same), are all engaged or married (all married prior to having a kid) and are now far better off financially than myself, a professor at a small university. This ain't rocket science, I just cant imagine for the life of me why we don't talk about this stuff in schools and families growing up, and why this is not explicitly preached from the pulpit in every church in America.

I would love to see this WC men data broken down by career, I have a hard time believing the data is nearly as pessimistic for plumbers and electricians as it is for those working in service jobs or the consistently unemployed.