How We Engineer the American Transition

The playbook from America's post-Civil War great reinvention—techno-nationalist acceleration paired with human-social formation

Many people think America is in decline, but what we are really in is a period of transition. Across a range of dimensions in our society - in culture and formation, institutions and governance, and political economy and material conditions - we are seeing the configurations of the previous order decaying or coming under stress. This presages a new, emerging America, but one that might well be much better than what came before. I discuss the idea of the American Transition in a recent post (complete with frameworks):

Today I want to dive into what it takes to successfully navigate a social transition and construct a successful new configuration, by looking back at a previous such transformation. This was the transition from the society of antebellum America, to that of post-Civil War America and the society built by the Second Industrial Revolution.

This transition occurred over the period of roughly 1860 to 1930. The advent of the Great Depression signaled the problems of the new order, inaugurating a new period of transition that created American society as we have personally known it, but I’ll have to cover that transition in a future post.

I’ll again commend Tanner Greer’s excellent essay on the making of a techno-nationalist elite that describes antebellum America as having people who saw themselves primarily as citizens of their state, each of which had its own insular elite. The economy was built around extractive industries like the southern slave economy (in which northern industries like New England textile mills were integrated) and elites who were suspicious of industrialization. Greer writes that their favored politicians, “dismantled America’s system of centralized finance, slashed its tariffs, vetoed internal improvements, shoved industrial policy down to the states, and maligned the rising class of industrialists.”

In my own essay on the managerial revolution, I describe the nature of the economy as basically a collection of small sole proprietorships and partnerships:

Prior to circa 1830, America was a capitalist country, but the economy consisted of a vast number of small-scale businesses or household enterprises. Only a handful of businesses – a couple of armories and textile mills – had as many as 100 employees. Essentially no businesses operated in a multi-site, multi-unit, or vertically integrated manner apart from the short-lived Second Bank of the United States. Production, distribution, and sales happened through market transactions, facilitated by an array of trading companies, jobbers, agents, etc.

In the Civil War and its aftermath, America saw a vast transformation to a new, integrated national identity and economy. This was increasingly shaped by technological advances, large scale corporations of the type we are familiar with, linked together by sophisticated new forms of infrastructure like railroads and telegraph lines.

This didn’t just happen. It had to be created. It required significant policy changes and government actions to facilitate it, the development of new financial institutions, etc. There was innovation across a whole range of domains, from technology to corporate forms.

But this “techno-nationalist” transformation had another side to it, which is figuring out how to help Americans adapt to this new world, and how to make sure that this new world actually benefitted the average citizen. Along with the Second Industrial Revolution, we also had the Progressive Movement, which, broadly understood, undertook the social side of this national transition.

In effect, the American transition proceeded along two tracks, one creating what we can call the Techno-Industrial Stack, the other the Human-Social Stack.

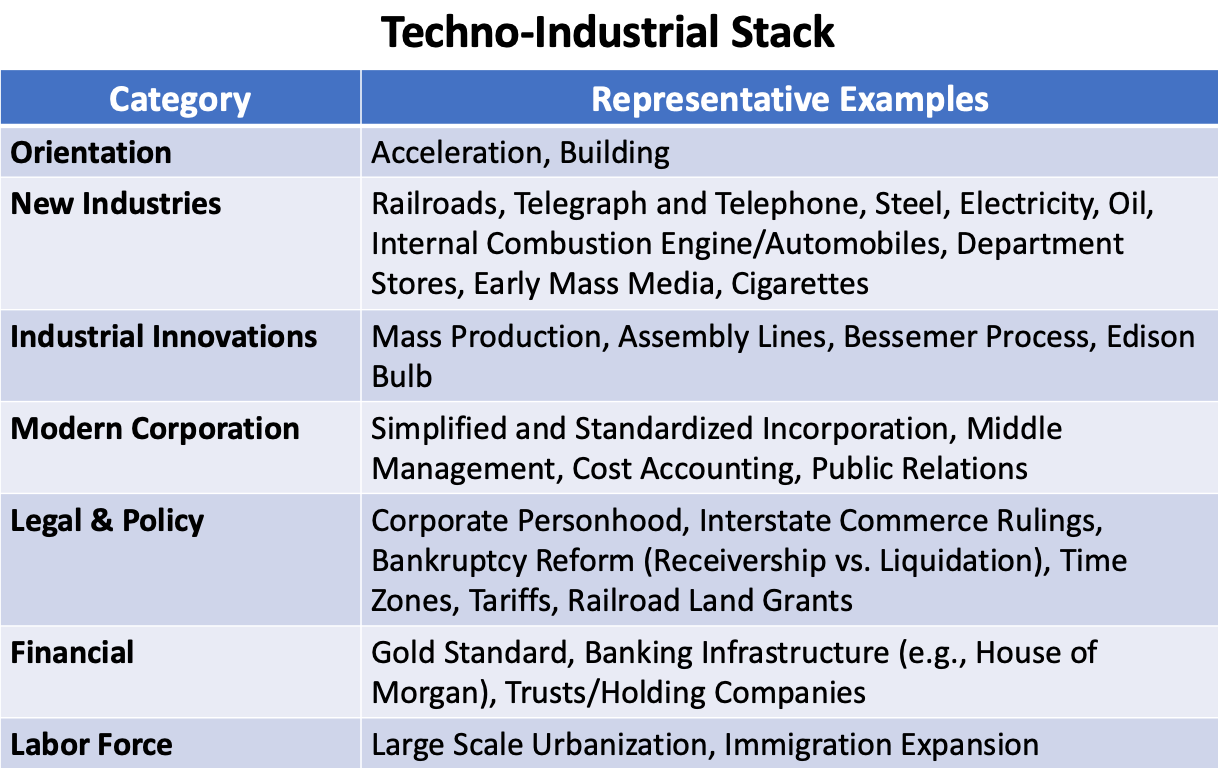

Here’s an example of what went into creating the Techno-Industrial Stack.

The orientation of those involved in this effort was towards technological and industrial acceleration, and about building - companies, infrastructure, etc. Numerous industrial innovations were created, and many new industries formed. The modern corporation with its layers of management and internal processes and controls began to emerge. The legal environment was transformed to be friendly to these types of institutions, which would have been largely illegal or difficult to establish in antebellum America. The finance world also developed in parallel to finance this. And the vast quantities of geographically concentrated labor needed for steel mills, auto factories, etc. were supplied by the stupendous growth of huge urban centers and mass immigration. Chicago, for example, went from 300,000 people in 1870 to 1.7 million people in 1900.

It’s important to note that not everything was positive about this. Perhaps the creation of the cigarette industry wasn’t one of our high points. There was also tremendous pollution, etc. And of course these firms created a lot of misery as well, and were known to abuse customers and employees. Hence the need for the Human-Social Stack.

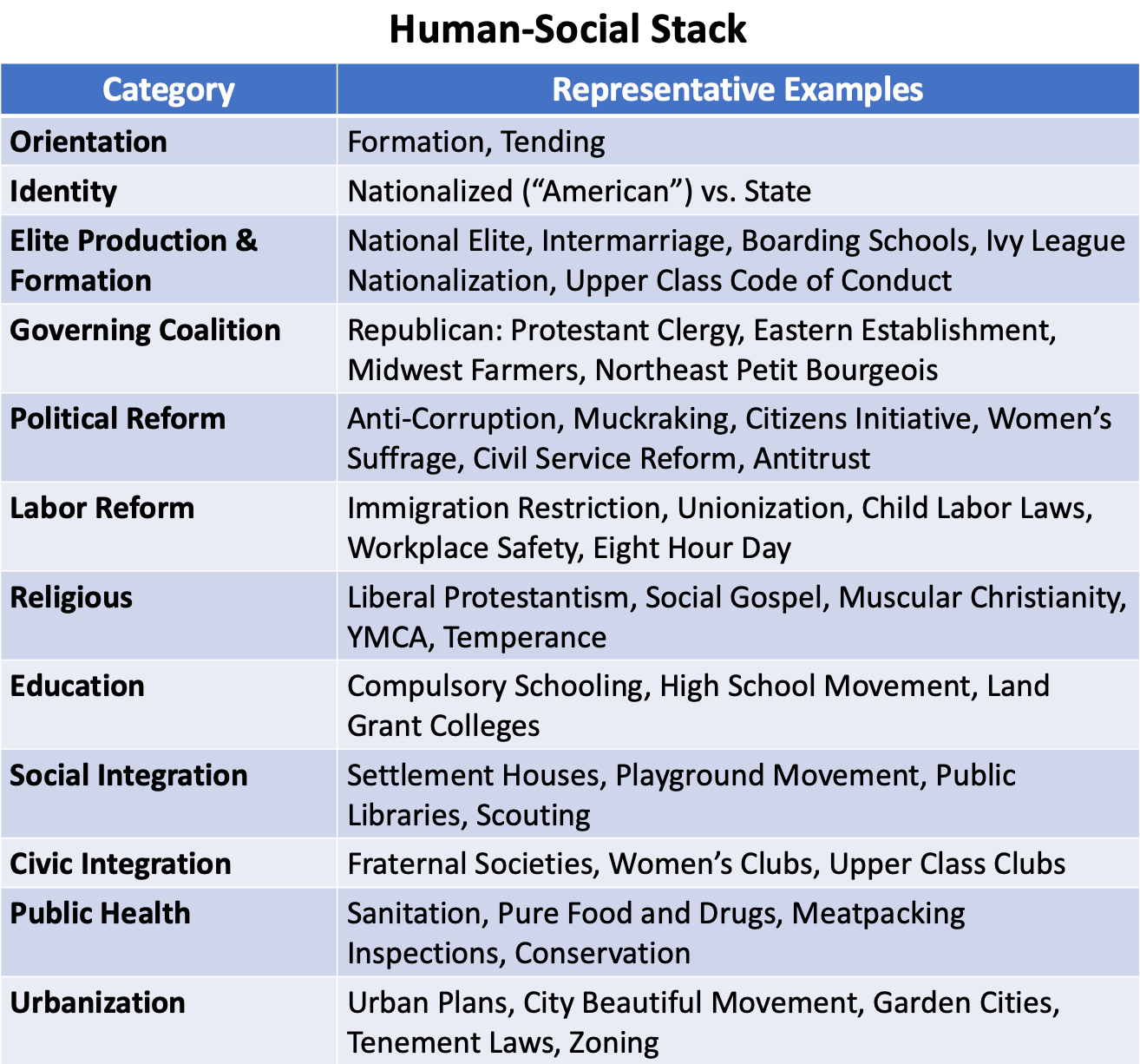

The creation of that Human-Social Stack was even more involved. Here’s some of what went into it.

The orientation of this stack was towards formation - of our people and institutions - and tending to their wellbeing. It created a new, national identity, a new elite (the WASPs/Eastern Establishment), and a stable governing coalition. There were reforms across a host of dimensions including politics, labor, civil society - even religion. There was a focus on formation of our people through upgraded education (e.g., the high school movement), integration of immigrants, etc. The negative effects of large-scale industrialization and urbanization were ameliorated through labor laws, unionization, sanitation, pure food and drug laws, antitrust etc.

Again, not all of these were positive. The encounter of Christianity with modern science was not resolved well in the form of liberal Christianity in my view. The temperance movement ultimately brought Prohibition, which proved unpopular. Similarly, I could have included something like eugenics on this list, which was fortunately ultimately rejected.

But while we could look back at this and criticize a lot of what happened, undoubtedly our leaders turned America into a great nation, a global powerhouse across multiple dimensions. And by and large they managed to overcome many of the problems and make this new America work for its people, not just for elites.

Today, we face a similar task of future building in America. We need to keep building the 21st century Techo-Industrial Stack - AI, autonomy, robotics, space, energy, biotechnology and surely much more. We also need to be building in parallel a Human-Social Stack that makes that technology work for our people, and helps our people get positioned for success in that world. We need acceleration, but also formation. It’s a time to build technology, but also to build up our people.

This transition takes place against the backdrop of competition with China, which is trying to beat us in this race, with a model that’s proven extremely effective in the techno-industrial sphere but dystopian in the human-social one.

Better American versions of these are not just going to appear. They have to be built. We will need solutions that span all of the different domains I highlighted in the two charts above, and probably more than that. Unfortunately, all too many of our debates today are either irrelevant to the task of actually building that future America, or are actively about trying to keep us from building it. We need to make sure we are focused on the right challenges and tasks.

One point that leaps out at me Aaron -

The techno-acceleration of the early 20th Century was labor-intensive. The human formation aspect of it was tied to the need for a vast amount of semi-skilled labor. This is why the Prussian Model Education became so prevalent in America; it promised to generate a large number of laborers capable of filling positions that required the ability to think and adapt to a machine-environment that had gotten more sophisticated than the old "human-machine" industries condemned by 19th Century socialists and liberals. The man who John Stuart Mill describes as mindlessly pulling the same lever every 15 seconds for ten hours a day didn't exist anymore. We needed factory workers with a high-school or vocational-technical education who could run a machine that required intelligent inputs.

But our current techno-acceleration is going in a direction that reduces labor-inputs. We don't need more people, we need a handful who are extremely well-trained. Whether we like it or not (and in many cases we don't) the direction is to replace labor with tech whenever possible. I'm convinced the only reason self-checkout has receded in some places is the degenerate morals of our society. AI is generating code and graphics that would have taken dozens of man-hours to generate. I'm entirely convinced that the university bubble is going to pop in the next twenty years and its replacement is going to be asynchronous, AI-generated, at-your-pace EduSlop, with maybe a token professor on the other end of 1000-student online sections to maintain plausible accreditation standards. Mass-education and personal education have become incompatible, technologically as well as in terms of philosophy of education.

So the problem becomes - what do we do with all the superfluous people who we don't need anymore to keep the system running? Permanent welfare class? Let me remind you of what happened when Rome did that. Government-generated make-work? We already have a civil service that does that, poorly. Massive, luxury, upper-class-oriented service sectors? Sounds like a recipe for a communist revolution. Decentralization of our global oligopolistic corporate economy into a cornucopia of small service providers? The elites will strangle this in its crib, just like Amazon and Google already did to the online economy of the Aughts and early 2010's.

Any sustainable human-social formation requires us to figure out how to solve the excess labor problem. "Let them learn to code" might sound funny to the editors at the New Yorker and Atlantic Weekly, but this is going to be the crisis of the 21st Century transition. I know the technocrats think we can rely on population decline to fix this in time, but the deliberate destruction of human capital sounds a lot like a kind if inverse-Luddism.

The positivity in this post is great to see. We need more people painting a vision of the future that is exciting and motivating.