Very often the actions we take in life are predicated on implicit answers to questions we never explicitly considered.

For example, how many people are included in the elect? I’d never really considered this question until I read Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age, in which he notes that historically in the West, the answer was very few (“narrow is the gate”). A good example of this in the Catholic tradition is the famous sermon “The Little Number of Those Who are Saved” by St. Leonard of Port Maurice.

Taylor also describes the Reform spirit in the late Middle Ages that became increasingly intolerant of two-speed Christianity. In the Church, there were elite Christians in the priesthood or monastery who lived lives fully devoted to Christ – in theory at least – and ordinary lay Christians in the world who adhered to a lower standard, too low in the view of these reformers, who wanted to raise them. This was one of the trends that led into the Protestant Reformation, which rejected the idea of two-speed Christianity entirely.

This leads to practical problems. As Taylor notes, “There seems to be a dilemma here, between demanding too much renunciation from the ordinary person, on the one hand, and relaxing these demands, but at the cost of a multi-speed system, on the other.”

He also notes that the original Protestant system, in rejecting two-speed Christianity, when faced with the choice between a low bar standard and a high bar one, selected the latter:

Radical Protestantism [Calvinism] utterly rejects the multi-speed system, and in the name of this abolishes the supposedly higher, renunciative vocations; but also builds renunciation into ordinary life. It avoids the second horn, but comes close to the first danger above, loading ordinary flourishing with a burden of renunciation it cannot carry. It in fact fills out the picture of what the properly sanctified life would be with a severe set of moral demands. This seems to be unavoidable in the logic of rejecting complementarity [of vocations], because if we really much hold that all vocations are equally demanding, and don’t want this to be a leveling down, then all must be at the most exigent pitch.

It strikes me that you can insist on a high bar standard if you believe the number of the elect is small. However, today we live in a quasi-universalist world. While few explicitly hazard a guess as to what share of people are elect, de facto Christian leaders behave as though the number of the saved is large.

So when you have a view that many or most people are elect, and you reject two-speed Christianity, then that leads to a very low bar standard for Christian life. And indeed, that’s what we see in both Evangelical and Catholic America today. Both of them have extremely low standards for being a member in good standing.

I suspect that if people today still believed the number of the elect was small, our churches would be much more demanding. While pastors today might profess not to know how many people are elect, they have some implicit answer to that question and that answer helps shape their ministry strategy.

What Is the Current Condition of the Church and American Society?

Another question that has profound implications for ministry strategy today is that of the condition of the church and also of American society. Is it good, bad, or in between? It is getting better or worse?

If you believe things are good or at least not deteriorating, then you are probably inclined to keep on with current strategies, maybe with some tweaks. You’re probably less willing to entertain radical or risky changes. On the other hand, if you think things are bad and getting worse, then your appetite for change and risk may go up.

Rod Dreher clearly believes things are bad and will only get worse from here. Hence his call for a Benedict Option that envisions some potentially radical changes to how the church is done today. He writes:

Could it be that the best way to fight the flood is to . . . stop fighting the flood? That is, to quit piling up sandbags and to build an ark in which to shelter until the water recedes and we can put our feet on dry land again? Rather than wasting energy and resources fighting unwinnable political battles, we should instead work on building communities, institutions, and networks of resistance that can outwit, outlast, and eventually overcome the occupation.

Dreher thinks Christianity needs to set a high bar, such as in his section saying, “Don’t compromise to keep the young.” His vision of the future is of a smaller but more robust church capable of riding through rough times. Note the ark imagery.

Many Evangelicals rejected the Benedict Option. I believe a big part of the reason why is that they simply reject Dreher’s premise that things are getting bad. Instead, if you listen to what they say and look at what they do, it’s pretty obvious that they think things are still going reasonably well. They still have big expansionist visions such converting significant percentages of people in their city, planting large numbers of new churches, etc. that at a minimum suggests that unlike Dreher, they believe Christianity is going to retain significant mainstream appeal. As a video put out by a Manhattan church plant put it, “We’re here because we refuse to believe that this city is hostile to church.”

The Cassandra Conundrum

One of the challenges Dreher ran into with reviewers of his book is that it’s hard in the Evangelical world to get a platform to speak without being very successful already. Successful people, by the very fact of being successful, are biased in favor of thinking conditions are good. Hence there is a structural bias against people who think the situation is bad getting a positive hearing.

There’s a big exception to this – politics, both electoral and within institutions and movements – where the people out of power, even if successful in their own right, are always going to argue things are bad as vector to obtaining power. So I don’t want to suggest that the successful always argue things are good. But it’s a situation that applies in some domains.

The Evangelical world, essentially all of the people with powerful platforms to speak are either a) pastors of very successful megachurches b) leaders of important Evangelical institutions c) their acolytes or others who hope to curry favor with them.

This isn’t the result of nefarious conspiracy but rather common sense. Who are you going to listen to, someone who is successful or someone who is a failure? Who is going to have a bigger audience, the pastor of a 50 person church or the pastor of a 5,000 person church?

Now ask, if you’ve built a 5,000 person megachurch in a major city, are you likely to think that Christianity is losing its appeal or that trends for the faith are poor in America? Probably not. If I were in the shoes of one of those pastors, I think I myself would probably say that things may be different today but they are still ok if we adjust our ministry strategy a bit – say to look more like mine.

The problem comes, as with the innovator’s dilemma in corporate America, when something is wrong but those who recognize it or propose innovative solutions can’t get a hearing because only the successful or representatives of the status quo have a voice. It’s no surprise to me to see that so many innovations and adaptations to new situations happen outside established institutions.

As Eric Hoffer put it in The Ordeal of Change, describing the importance of the role of the “unfit” (his term) in human progress:

It is not usually the successful who advocate drastic social reforms, plunge into new undertakings in business and industry, go out to tame the wilderness, or evolve new modes of expression in literature, art, music, etc. People who make good usually stay where they are and go on doing more and better what they know how to do well.

So no surprise that the people writing book reviews often had a negative view of the Benedict Option. They are representatives of the status quo because they represent, in general, successful institutions.

This is related to what I wrote about in Newsletter #13 between the difference between the “neutral world” (the world is neutral towards Christianity) the “negative world” (the world is negative towards Christianity). Most of the Evangelical leadership class is still in a neutral world, or even a positive world, mode. Dreher is in a negative world mode. Before debating whether or not the Benedict Option is the right solution, there first has to be agreement on the problem. This is where I think their real disagreement with Dreher is. The critics may target the various elements of his solution but ultimately they don’t agree on his assessment of the position of the church today. I do know any number of Evangelicals who agree with Dreher on his assessment of the church’s condition (if not necessarily his prescriptions), but they either aren’t blogging for the big sites or keep their opinions to themselves in public.

What’s more, Dreher’s statements about the condition of the church today, if true, can’t help but implicate them as the culprits, at least in part, because they were the ones running the show while things were crumbling and who had launched and implemented all of those strategies like political activism that Dreher now says should be abandoned. That certainly isn’t likely to be well received, not by any of us if we were in that position.

Dreher is an interesting case in that he is someone who has success and a big platform and yet is something of a prophet of woes to come. It’s no surprise to me that he became alienated from the church during his reporting on the Catholic sex abuse scandals. It seems to be largely people who have had some experience like that which disassociated them from their previous identification with the church who publicly put out negative diagnoses of it.

As Ross Douthat wrote in a column last year:

The first time I ever heard the truth about Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, the former archbishop of Washington, D.C., finally exposed as a sexual predator years into his retirement, I thought I was listening to a paranoiac rant.

It was the early 2000s, I was attending some earnest panel on religion, and I was accosted by a type who haunts such events — gaunt, intense, with a litany of esoteric grievances. He was a traditionalist Catholic, a figure from the church’s fringes, and he had a lot to say, as I tried to disentangle from him, about corruption in the Catholic clergy. The scandals in Boston had broken, so some of what he said was familiar, but he kept going, into a rant about Cardinal McCarrick: Did you know he makes seminarians sleep with him? Invites them to his beach house, gets in bed with them …

At this I gave him the brushoff that you give the monomaniacal and slipped out.

That was before I realized that if you wanted the truth about corruption in the Catholic Church, you had to listen to the extreme-seeming types, traditionalists and radicals, because they were the only ones sufficiently alienated from the institution to actually dig into its rot. (This lesson has application well beyond Catholicism.)

As Douthat notes, these folks also tend to be, shall we say, quirky, which allows them to easily be dismissed by people who aren’t interested in what they have to say.

In summary, we need to think about how people answer various foundational questions that may not be explicit – that is, to understand their unstated assumptions – when assessing the things they are telling us. Often disagreements are a result of conflicts over implicit premises never directly stated. And we should understand that the people who are successful or in positions of power often have a bias against messages of critique about the state of the organization or movement.

I would also encourage you to think explicitly about your own personal position on the question of the state of the church and society because this will inform at a base level every single thing you do.

My Own Take

Since I raised this topic, I’ll put my own cards on the table. Obviously, I see that the condition of the church’s teachings towards men is bad, as I’ve written about it at length here in my newsletter. I also think things are worse than commonly believed in both society and the church generally, and heading the wrong direction.

With society, we’ve been here before. Periodically, about once every human lifespan, America has gone through major resets in our system precipitated by problems the old regime couldn’t solve. The first was the period from the Revolution through to the Constitution. The second was the Civil War. The third was the New Deal through the postwar settlement.

From the Constitution to the end of the Civil War: 76 years (1789-1865)

From the Civil War to the end of WW II: 80 years (1865-1945)

From WW II to today: 74 years (1945-2019)

Our postwar regime is coming due for a reset. Previous resets have involved existential wars. I hope that doesn’t happen this time. But regardless of whether we are heading for a major reset or just going through more minor turbulence, the fact that previous generations did navigate these crises successfully should give some hope for this time around. Just because a successful reset does occur, however, doesn’t necessarily mean that any of us will like the resulting regime.

As for the church, I don’t have any neat historical lessons to offer. As I’ve indicated multiple times in this newsletter, I think our task to make an accurate diagnosis and create strategies that are relevant and have a chance of working in the current age. I have some ideas in development that I plan to share in future newsletters.

The Faux Negativists

There’s another category of people I should perhaps mention. It’s those who seem to have an extremely negative diagnosis of the church, society, etc. but whose solutions don’t match their purported claims.

A good example is Patrick Deneen and his book Why Liberalism Failed. The book is a blistering attack on liberalism as an intrinsically flawed ideology that has produced innumerable bad outcomes.

And, yet, what is his solution? Neo-Tocquevillianism and neo-Tocquevillianism alone.

A better course will consist in smaller, local forms of resistance: practices more than theories, the building of resilient new cultures against the anticulture of liberalism. When Alexis de Tocqueville visited America in the early decades of the nineteenth century, he observed that Americans tended to act differently from and better than their individualistic and selfish ideology. “They do more honor to their philosophy than to themselves,” he wrote. What’s needed now is not to perfect our philosophy any further but to again do more honor to ourselves. Out of the fostering of new and better selves, porously invested in the fate of other selves—through the cultivation of cultures of community, care, self-sacrifice, and small-scale democracy—a better practice might arise, and from it, ultimately, perhaps a better theory than the failing project of liberalism.

Tocqueville’s pre-industrial America is long dead and buried (see Newsletter #26: The Fall of the Household). Nevertheless, it’s hard to argue against Deneen’s ideas for rebuilding small-scale communities. That’s something I endorse. It may well also be that it’s not obvious what to do beyond that.

But Deneen isn’t embracing neo-Tocquevillianism because he’s not yet sure what else to do. He’s explicitly delegitimizing any other form of dissent from the liberal regime he decries. He says:

A rejection of the world’s first and last remaining ideology does not entail its replacement with a new and doubtless not very different ideology. Political revolution to overturn a revolutionary order would produce only disorder and misery.

He rules out attempting to replace or reform liberalism. This passage technically leaves open the possibility of replacing liberalism with a non-ideological regime. But later he explicitly closes the door on that, saying:

We can either elect a future of self-limitation born of the practice and experience of self-governance in local communities, or we can back inexorably into a future in which extreme license coexists with extreme oppression.

Really? Those are the only two possible futures that exist? I don’t think so.

There’s an immense range of possible futures. Some of them might indeed be bad, some no doubt much worse than today. But are there truly no solutions we can seek that might not be better than today’s regime? This is a classic false dilemma.

Deneen’s book is thus not just a critique of liberalism. Much more importantly it is a book about delineating the acceptable boundaries of dissent from liberalism, which he draws at the borders of neo-Tocquevillianism. It is part of a genre of conservative writing that is concerned with border policing.

It should come as no surprise that Deenen has not to the best of my knowledge experienced any of the deplatforming attempts that have hit many other people. The liberal regime he’s supposedly attacking recognizes very well that he’s no threat to it.

Like a lightning rod, Deneen’s book draws in people who sense there might be something fundamentally wrong with our world, then channels their potential dissent harmlessly into the ground in the form of neo-Tocquevillianism, dissuading them from any action that might actually try to fundamentally change things.

Whenever you see a strongly negative diagnosis paired with proposed remedies that don’t match the portrayed magnitude of the problem, that’s a yellow flag. It doesn’t necessarily mean the work is flawed or useless. Deneen’s book contains much that is excellent. But it’s a signal to us to be very careful readers.

Your Positive Family Stories

It’s a tough world out there (see above). But I continue to believe that marriage with, if possible, children is the best path for most even if it’s a higher risk course than it used to be. A problem is that too many people in happy marriages are keeping their lamp under a bushel. We see and read so many negative stories about marriage and family life, but there’s much joy and so many good things that come from family that too often don’t get reported (see Newsletter #28). So I have been trying to include positive family stories and great family photos in my newsletters to make sure we are spreading positive vibes not just negative critiques. If you have a story or picture you’d like to share, send it my way.

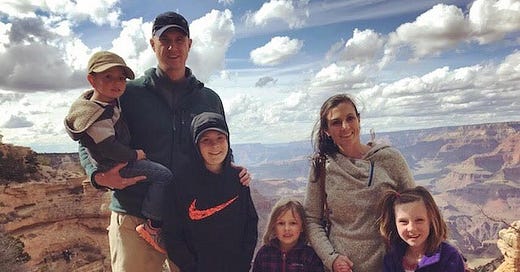

This month a picture and story from reader Nate:

I’ve enjoyed reading your newsletter, and especially your note on the joys of family life. I’m attaching a photo of our family from the Grand Canyon this spring. (Yes, I know you said “no pictures of vacations.” But one the great joys of family is family trips).

We live in small-town Wyoming, where I have a law practice. My wife is a stay-at-home mom, and also an awesome piano teacher. She gives piano lessons to about 8 other kids in our community. Each week, we invite those kids into our living room where the piano is, and my wife gives a half-hour lesson. During the lesson, I take our children to the other room or basement for a half-hour of uninterrupted time with Dad. No screens. No distractions. Keep out of Mom’s hair while she gives the lesson. All the while, we can hear in the background the student working through the lesson and my wife’s patient responses with the student. When finished, our children receive their piano lesson (some more willingly than others). At the end of the school year, we invite the student’s parents and family into our home for a piano recital. It’s cramped in our living room with so many people, but everyone is always in high spirits.

The whole process fills me with joy. Joy that we are inviting the community into our home. Joy that my wife builds our home. Joy that I’m with my family. Joy that I can provide for them.

I have many specific instances of experiencing the joy of family. But this one stands out.

Noteworthy

Alastair Roberts: The Church and the Natural Family

NYT: How Parents Are Robbing Their Children of Adulthood – Today’s “snowplow parents” keep their children’s futures obstacle-free — even when it means crossing ethical and legal boundaries.

NYT: Human Contact Is Now a Luxury Good – Screens used to be for the elite. Now avoiding them is a status symbol.

SCMP: Too many men – China and India battle with the consequences of gender imbalance

Coda

We should stop trying to meet the world on its own terms and focus on building up fidelity in distinct community. Instead of being seeker-friendly, we should be finder-friendly, offering those who come to us a new and different way of life. It must be a way of life shaped by the biblical story and practices that keep us firmly focused on the truths of that story in a world that wants to obscure them and make us forget. It must be a way of life marked by stability and order and achieved through the steady work, both communal and individual, of prayer, asceticism, and service to others—exactly what liquid modernity cannot provide. A church that looks and talks and sounds just like the world has no reason to exist. A church that does not emphasize asceticism and discipleship is as pointless as a football coaching staff that doesn’t care if its players show up for practice. And though liturgy by itself is not enough, a church that neglects to involve the body in worship is going to find it increasingly difficult to get bodies into services on Sunday morning as America moves further into post-Christianity.

– Rod Dreher, The Benedict Option

Thank you for linking to this older article. Your critique of Deneen is interesting. You're right that to close the door on replacing or reforming liberalism doesn't make sense. Why are we even discussing the problem at all then?

But given the scope of liberalism's problems, and its powerful entrenchment across public and private spheres, a degree of "neo-tocquevillianism" seems like wisdom does it not? Pre-industrial society isn't coming back but I would argue that until men and women make the changes in their personal lives that bring about smaller forms of community within modern society, and lessen liberalism's hold on them, it will be next to impossible to challenge liberalism successfully. We have to start from a place of strength and individual, community-less people do not have much strength.